The perennial complaint about watch-list filtering is

that there are "too many false alerts". Before we can deal with this, we must

define what we mean by a false alert and what the client means by "too many".

Unfortunately, the alert handlers only see the alerts, of which it is quite

normal for 99% or more to be eventually identified as false. They forget

completely the 97% or more customer names and transactions that the software

passed automatically and which, without the software, they would have had to

examine individually. So, for example, if the alert rate is a reasonable 3%, a

screening of 10000 customers or transactions would be expected to generate 300

alerts. That means there are 9700 decisions that have been made without human

intervention. If, of those 300, maybe 3 are expected to actually be the people

on the list, this is still only 297 instead of 10000 that have required manual

intervention to pass them. The first stage in managing the user expectation is

to point out the number of decisions they don’t have to take at all, which is

normally many more than those they have to take that turn our to be

false.

The second part of managing false alerts needs, I believe, a new

definition. This I call a "Valid Alert". A valid alert is one that we expect the

software to generate.

Any string matching/search software has limitations,

particularly when looking for “close” as well as exact matches. In fact, with

name searches, even exact matches can turn out to be false, names are not unique

identifiers. If there is a John Smith living in London, UK on the list and there

is a John Smith living in London, UK who is a customer then, if the filter only

checks Name, City and Country an alert will be raised against this

customer, even if he is not the same John Smith. In this case, despite the alert

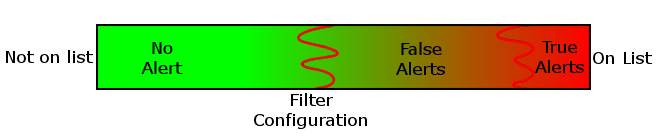

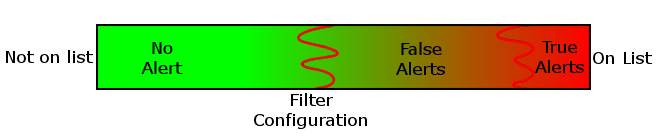

being false, it is still valid that the software raised it. The diagram below

illustrates the possibilities for watch-list filtering.

The extreme left

represents names that are not on the reference list, the extreme right those who

are. Between these extremes, there are three regions:

- True Alerts, names similar to those on the list that turn out to be the same person/organisation;

- False Alerts, names similar to those on the screen list that turn out not to be the same person/organistation and

- No Alert, names dissimilar enough to those on the list that they do not create an alert at all.

The False and True alerts together consitiute what I call Valid alerts; those we want the software to generate.

However, the boundaries of these regions are not well defined. The difference between a True and False alert can only be

decided by reference to the Customer Due Diligence carried out on the customer

to verify that they are a reputable person. It is both possible that a

person with a name very close to that on a list, or even an exact match, is not

the same person or that a person with a name which doesn’t appear to be a close

match is in fact, the criminal against whom a sanction applies.

The border between an alert being raised or not is defined by the way the filter is configured. In some

cases, for example domestic PEPs, it can be required that an alert is not

raised even if the customer is the person on the list. The

challenge is to agree with the business what is an acceptable Valid alert and so

configure the filter to move the boundary between No Alert and False Alert as

far to the right as possible without, of course, introducing a risk of missing a

true alert.

The important point here is the agreement with the business. This is not a purely technical decision. Every business will have a different

risk appetite and a different perception of the cost-benefit of employing alert

handlers against risking missing true alert. A small private bank with 1000

high net-worth customers could probably accept a 10% alert rate – 100 alerts is

not a huge number to deal with and the money laundering risk in private banking

is high. A large retail bank with 10 million low risk customers would have to

employ a whole department of alert handlers to deal with 1 million alerts and

might never catch up a backlog, so they would be looking for a much smaller

alert rate. The definition of what makes a valid alert is not fixed, but dependent on the perception of the business.

more..